Mental Health in Schools: Moving Stigma Out in the Open

Since the start of the pandemic, rates of psychological distress and chronic mental health issues among young people have increased. In New York, state officials estimate that one in five children ages 2-17 has one or more emotional, behavioral, or developmental condition while approximately 264,000 New York kids ages 9-17 have a serious emotional disturbance that substantially limits their ability to function (Kramer, 2021). Across the USA, 51% of 11-17-year-olds who participated in MHA Screening reported having thoughts of suicide or self-harm more than half the time, or nearly every day of the previous two weeks, totaling nearly 160,000 youth (MHA, 2022). From March to October of 2020, children’s visits to the emergency room for mental health conditions increased 31% for those 12-17 years old and also increased 24% for children ages 5-11 compared to the same period in 2019 (MHA, 2022).

As the pandemic continues, mental health agencies are faced with growing waiting lists, shortages of qualified mental health staff, and alarming rates of suicide ideation in their communities. These longstanding issues are compounded by the impact of stigma that saddles our troubled youth. It is rare that an adolescent will seek services at mental health programs or schools if stigmatization persists, and so it is imperative that stigma be addressed. By leveraging resources, modifying mental health messaging, and promoting wellbeing, schools can provide a safe space for youth to help them overcome stigma-related, psychological barriers to seeking support.

Stigma can be defined as negative, judgmental, and/or discriminatory attitudes toward mental health challenges and those who live with them (MHA, 2022). It stems from myths, inaccurate perceptions and lack of information. Stigma is often a key problem for young people experiencing a struggle with their mental health as it prevents them from getting needed support from family, friends, and services. Sometimes seeking help can expose youth to the risk of discouraging, unsupportive reactions from others, especially surrounded by peers and family naysayers. This peer pressure can make someone less inclined to talk about what they have been going through. (Psyche, 2022). For many, the consequences of stigma can include: limited social engagement or greater social exclusion, decrease self-efficacy, and increase social isolation and withdrawal.

In contrast, taking the opportunity to talk about challenges with emotional and psychological issues has the potential to deepen relationships. Teens who share their experience often feel less burdened about having a “secret identity” and feel that they get to live more authentically. The act of sharing can also lead to the relief that comes from being truly listened to when feeling down or anxious, or a meaningful connection to other people or services that can provide help (Corrigan, 2016).

Anti-Stigma in Schools

It has been widely accepted that mental health programs in schools increase resiliency and help-seeking behavior, and has the potential to make seeking help a universal intervention for all. Schools are on the frontline for identification of at-risk or presenting behavioral health concerns and have become the logical point of entry to addressing student wellbeing (NCSMH, 2013). Only 43.3% of all youth diagnosed with a major depressive episode in 2019 received any mental health treatment. Of those who receive mental health services, 70-80% of youth received them at school (MHA, 2022).

Making services visible and available in schools not only increases access and follow-up for all, but also reduces the stigma associated with mental health problems. Stigma reduction starts with school-wide promotional activities that enhance positive social emotional skills of all students regardless of whether they are at-risk for mental health problems. Fostering more positive attitudes and beliefs surrounding mental health topics lessens the emotional burden of shame and stigma. This can be done universally with age appropriate mental health education lessons and classroom-based social emotional learning (SEL) for all students.

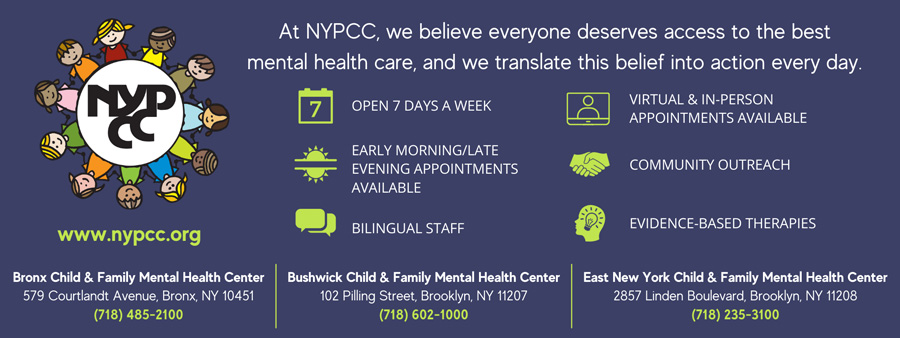

One of the key domains in any school mental health program is community coordination and collaboration with community-based mental health and social service organizations that are familiar with the culture and language needs of diverse student and family groups within the school (NASBHC, 2007). Programs like New York Psychotherapy and Counseling Center (NYPCC) build capacity for the school community to address stigma in diverse ways. For example, leading experts in an informal, positive environment facilitate workshops for parents on current topics. Offering free trainings to school support staff increases equips them with the knowledge and interventions to address important emotional needs. Additionally, establishing Community Outreach Teams that links mental health services and resources to schools in high needs areas or creating anti-bullying coalitions that raise awareness and support schools’ communities with strategies to deal with bullying – these types of services not only extend the scope of resources and finite capacity of the school, but also normalize that mental health issues can be addressed without shame or discrimination.

Mental Health Literacy

Mental Health Literacy can be defined as knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders that aid their recognition, management, or prevention (Jorm, Korten and Jacomb, 1997a). Improving mental health literacy among youth in schools is a promising alternative in the fight against stigma. New York State recently passed legislation to add mental health education to existing curricula, requiring that mental health education is integrated at all school levels. With this expansion, it is expected that the entire school community will be more adept at openly discussing mental health challenges, which, in turn, positively impacts youth ability to seek help.

The stigma of mental illness is embedded in our lives and comes in many forms. Using words like crazy, nuts, weird, what’s wrong with you or insane – can make people feel ashamed, hurt, and prevent them from receiving help. Students are already grappling with multiple stressors – defining their identities, coping with conflicts that might be happening at home, community violence, racial barriers, and heightened social anxieties – using disparaging language about emotional needs exacerbates the situation (Dillard, 2019). Generalizable terms like stress and stressed out, nervous, and feeling down, are more suitable. Integrating mental health literacy into school culture ensures we are using the right words to describe the various components of mental health.

Effective school mental health requires the involvement of many partners, with varied professional backgrounds, often working across sectors and disciplines. At times, differences in language and understandings can interfere with an integrated approach to care. It is helpful to work towards shared meanings across the school and with partner organizations. This includes stopping the use of stigmatizing language and educating others about its impact.

Staff members’ knowledge, beliefs and attitudes about mental health can influence their work with students. Professional training in this area should begin with basic mental health awareness and stigma reduction. Staff’s views on mental health form the basis for how they operate as confidantes, role models, and enablers of support. It is recommended that when staff hears stigmatized language: it should be identified, educate why it may be harmful, and replace the language with something more acceptable (MHTTC, 2021).

Closing Thoughts

Investing in mental health promotion and prevention results in cost savings by reducing or eliminating the need for more expensive intensive services. Furthermore, interventions like mindfulness techniques in the classroom, discussions about the stigma associated with mental illness, and student lead presentations on the importance of healthy coping strategies can decrease stigma and promote well-being for both students and staff. Students need be healthy enough to learn, and teachers need to be healthy enough to teach. Creating a stigma-free environment where the mental well-being of all is valued and fostered is essential to helping youth feel safe and accepted.

Scott Bloom, LCSW, is Director of Special Projects & Initiatives at the New York Psychotherapy and Counseling Center (NYPCC). For more information, call (347) 352-1518 or email SBloom@nypcc.org.

References

Corrigan, P. (February 1, 2016). Lessons Learned from Unintended Consequences about Erasing the Stigma of Mental Illness. World Psychiatry.

Dillard, Coshandra. Demystifying the Mind. Learning for Justice. Issue 61, Spring 2019.

Harsell, Chris, and Doster, Marvis. CARN Mountain Plains Mental Health Technology Transfer Center. Mountain Plains Mental Health Technical Transfer Center. 2022.

Jacobson, Rae; How to Talk About Mental Health Issues. Retrieved from https://childmind.org/article/talk-mental-health-issues/. May 2022

Jorm, A. F., Korten, A. E., Jacomb, P. A., et al (1997a) Mental health literacy: a survey of the public’s ability to recognize mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Medical Journal of Australia, 166, 182–186.

Kramer, Abigail. Kids Mental Health, by the Numbers. The Center for New York City Affairs. October 2021.

Kundert, Carla & Corrigan, Patrick W. May 25, 2022. How To Talk About Your Mental Illness. Psyche Newsletter.

Make It Ok (https://makeitok.org)

Macias, Maximillian and Nemer, Shannon; Classroom Wise. The Mental Health Technical Transfer Center Network and The National Center for School Mental Health; https://www.classroomwise.org. 2019.

Mental Health America. Mental Health Glossary. https://mhanational.org/terms-know-mental-health-glossary. May 2022.

Mental Health America. Youth in Crisis. https://mhanational.org/YouthinCrisis. May 2022.

National Center for School Mental Health. The Impact of School Mental Health: Educational, Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Outcomes. University of Maryland School of Medicine. http://mdbehavioralhealth.com/downloads/3716/CSMH+SMH+Impact+Summary+July+2013+.pdf?1496239910. 2013.

National Assembly on School-Based Health Care. (March 2007). Mental Health Planning and Evaluation Template. National Assembly on School-Based Health Care. (March 2007). Mental Health Planning and Evaluation Template.

National Center for School Mental Health. (2020). School Mental Health Quality Guide: Mental Health Promotion Services & Supports (Tier 1). NCSMH, University of Maryland School of Medicine. https://www.schoolmentalhealth.org/media/SOM/Microsites/NCSMH/Documents/Quality-Guides/Tier-1-Quality-Guide-1.29.20.pdf

New York State Education Department. (July 2018). Mental Health Education Literacy in Schools: Linking To A Continuum of Well-Being Comprehensive Guide. http://www.nysed.gov/common/nysed/files/programs/curriculum-instruction/continuumofwellbeingguide.pdf

Teen Mental Health (www.teenmentalhealth.org)